Why aren't all children in Tanzania attending secondary school?

On 27th November 2015, the Tanzanian government abolished all secondary school fees in order to increase accessibility to secondary education. However, many children still struggle to enter or complete secondary education. Research carried out by UNICEF found that:

- Around 2 million children between 7-13 years old are not in school

- Almost 70% of 14 to 17-year-olds are not enrolled in secondary education

- Only 3.2% of 14 to 17-year olds are enrolled for the final two years of schooling

So, what factors are contributing to the low rates of secondary education in Tanzania?

Education-related costs

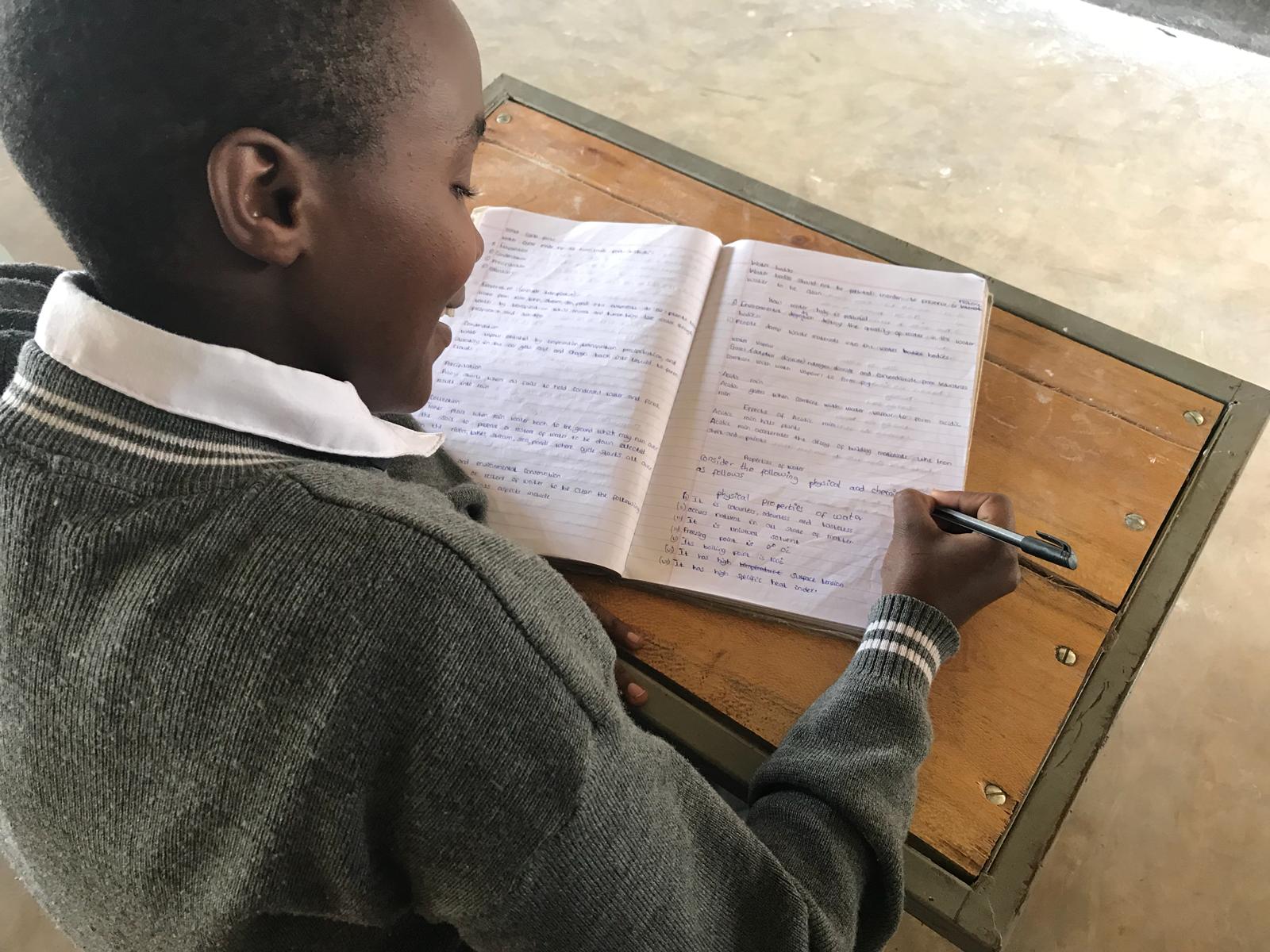

Whilst the 2015 policy has removed the secondary education fee, there are other costs that make it difficult for children from poorer families to go to school. Families have to pay for school uniforms and learning materials and, in rural Tanzania in particular, transport to and from school costs money as well. If transport isn’t a viable option, families may have to pay for their children to live nearer the school during term time. All of these costs mean that secondary education is still not affordable for a lot of families.

Insufficient school budgets

Previously, secondary schools would be funded by the fees paid by children’s families. However, the 2015 policy change means that this funding source has been cut off and, although the government has distributed money to cover this, schools aren’t getting enough income to maintain buildings, pay staff or provide learning materials. UNICEF says that the pupil-to-qualified teacher ratio is 131:1 in Tanzania, with the ratio at 24:1 in private schools and 169:1 in public schools. Moreover, the average class size is 70, more than 2.5 times the Sustainable Development Goal target of 27-28 pupils per class (Human Rights Watch).

The above statistics show that schools need more money in order to employ more qualified teachers to ease the burden on staff members. Greater income would also allow schools to build and maintain the necessary infrastructure that will allow more children to attend school. It may also allow schools to supply accommodation for children travelling long distances from rural areas because, as yet, the government hasn’t fulfilled its plan to build safe accommodation nearer schools, especially for girls.

Lack of provision for disabled students

According to UNICEF, around 7.9% of Tanzanians have a disability, but less than 1% of children in schools have a disability. This suggests that there is a large number of children with disabilities that are not in school for one reason or another. Human Rights Watch says that many schools do not have the facilities to help these children; specifically, there are not enough specialised staff that know how to

facilitate their learning. Furthermore, these children face discrimination which leads to many of them not attending to save themselves from the abuse.

Harassment, discrimination and expulsion of girls

Human Rights Watch says that less than one-third of girls that enter lower secondary education actually graduate at the end. Teenage pregnancies may be a significant factor in this, as UNICEF found that adolescent pregnancies caused almost 3,700 girls to drop out of education in 2016. UNICEF also found that more than one-third of girls in Tanzania are married before they are 18, with girls from poorer families twice as likely to be married before they are 18 than girls from richer families.

Many schools force girls to take pregnancy tests and expel them if they are pregnant. After being expelled, re-entry is made difficult by readmission costs, no readmission policy for young mothers, and a socio-cultural stigma that does not view young mothers in a positive light.

Pregnancy aside, girls face sexual harassment both in school, by teachers, and out of school, by other ‘responsible’ adults such as bus drivers. These activities are often unreported and are not dealt with properly, allowing more and more people to get away with them. This is, perhaps, not helped by the fact that many schools do not have a confidential reporting system in place that students can reach out to for support.

Difficult entry and re-entry

According to Human Rights Watch, more than 1.6 million students were denied entry into secondary education between 2012 and 2016 because they had failed the compulsory ‘Primary School Leaving Examination’ (PSLE). This test is used by the government to control the number of people entering secondary education, but for what reason? If education is so important for escaping poverty and improving the country’s economy, why would the government deny children access to it?

For students who have been expelled for one reason or another, it’s even harder to get back in. Re-admissions are extremely rare, which leaves children with few other choices. They could continue their education via private tuition, but this comes at a hefty price. Besides education, vocational training opportunities are not available to those who haven’t completed secondary education. The limited range of options increases the likelihood of remaining in the poverty cycle.

Poor quality of education

Despite all of the aforementioned factors, educational institutes will ultimately be judged on their academic success. Unfortunately, in Tanzania, the quality of secondary education is a major concern, with students showing poor literacy, numeracy and life skills. According to UNICEF, the 2014 PSLE results showed that only 8% of Grade 2 (UK equivalent: Year 2) pupils could read properly, only 8% could add or subtract, and less than 0.1% showed a high level of ‘life skills’ (defined as ‘academic grit’, self-confidence and problem-solving).

Many schools are not helped in this department by a lack of qualified teachers, especially in Maths and Science. The best teachers may have been turned towards private tuition, which is generally of better quality for students but much more expensive. Therefore, perhaps what is required is a better pay structure for teachers in public schools to attract them towards public teaching.

Furthermore, students are not helped by a lack of infrastructure, facilities and learning support at school. As we have discussed, classrooms are insufficient, student-to-teacher ratios are astonishingly high, learning materials are in short supply and there aren’t enough staff to support students with non-education issues. During secondary education, students have to take two compulsory tests, but a lack of quality education means they often fail and are forced to drop out.

Conclusion

Whilst significant progress has been made in the Tanzanian education sector for the past 15 years or so, most of these improvements have been seen in primary education. The benefits of a full secondary education include the possibility of a child being able to break their family out of the poverty cycle.

The removal of secondary school fees in 2015 is a step in the right direction, however, children still face many obstacles that are hindering their progress through secondary education. One of the most significant factors is the additional costs incurred by transport, learning materials and school uniforms. Moreover, there is lack of teaching infrastructure and support for a wide range of students and a lack of quality teaching overall.

Secondary education may now be free for all children, but there is a wide range of problems that need addressing to ensure that all of these children are managing to access the education that they have a right to.

You can visit Ollie's blog by clicking here